DESPITE academic studies noting the harms associated with corporal punishment, U.S. public schools use it to discipline tens of thousands of students each year, data from the U.S. Department of Education show.

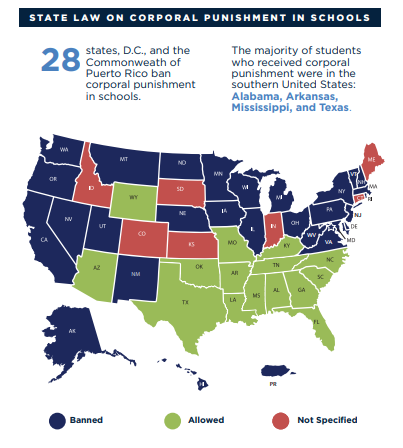

Public schools in 22 states reported using physical discipline to control student behavior during the 2017-18 academic year, the most recent year for which national data is available. Twenty-eight states have banned corporal punishment in public schools, but 15 have laws giving public schools explicit authority to use it and seven states have no laws allowing or prohibiting it, according to a September 2022 report from the education department’s Office for Civil Rights.

Meanwhile, corporal punishment is legal in all private schools, except for those in Iowa and New Jersey.

It’s not yet clear whether schools have relied on this type of discipline more or less often amid the COVID-19 pandemic. However, school district officials reported a marked increase in student misbehavior in 2021-22, compared with before the coronavirus arrived in the U.S. in 2019. News stories and research studies have documented the pandemic’s widespread effects on kids’ mental and physical health.

When the U.S. Department of Education surveyed public school districts in 2022, 84% agreed or strongly agreed the pandemic has negatively affected students’ behavioral development.

Almost 6 out of 10 public schools reported “increased incidents of classroom disruptions from student misconduct” and 48% reported increased “acts of disrespect towards teachers and staff.” About half reported more “rowdiness outside of the classroom.”

Even if the number of children physically punished at school has fallen in recent years, the issue warrants journalists’ attention considering the serious injuries students sometimes suffer and the fact that Black children and children with mental or physical disabilities have, for many years, received a disproportionate share of school corporal punishment.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, 2022.

The federal government requires public schools and public preschools to report the number of students who receive physical punishment. In 2017-18, public schools physically disciplined a total of 69,492 students at least once — down from 92,479 kids in 2015-16. The practice was most common in Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas and Oklahoma.

That year, public preschool programs, which are often housed within public elementary schools, reported using corporal punishment on a combined 851 children aged 3 to 5 years.

It’s unclear how common corporal punishment is in private schools because the federal government does not require them to report their numbers. Elizabeth Gershoff, one of the country’s foremost experts on corporal punishment, says she knows of no government agency or organization that tracks that information.

She urges journalists to help their audiences understand the various ways schools use physical discipline and its potential impacts on student behavior, mental and physical health, and academic achievement.

“Spanking is a euphemism for hitting,” says Gershoff, a professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. “Spanking and paddling — people use those words to minimize the aggression we are using against kids.”

The global use of school corporal punishment

The U.S. is the only member of the United Nations that has not yet ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international treaty adopted in 1989 that, among other things, protects children “from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation.” Somalia ratified the convention in 2015 — the 196th country to do so.

Globally, about half of all children aged 6 to 17 years live in countries where school corporal punishment is “not fully prohibited,” according to the World Health Organization.

But legal bans do not necessarily mean corporal punishment ceases to exist, a team of researchers from the University of Cape Town learned after examining 53 peer-reviewed studies conducted in various parts of the planet and published between 1980 and 2017.

In South Africa, for instance, half of students reported being corporally punished at school despite a ban instituted in 1996, the researchers note.

“There is also concern that school staff and administrators may underreport school corporal punishment even where it is legal,” they write, adding that a study in Tanzania found that students tended to report twice as much corporal punishment as teachers.

While there’s limited research on corporal punishment in U.S. schools, numerous studies of corporal punishment in U.S. homes have determined it is associated with a range of harms. When Gershoff and fellow researcher Andrew Grogan-Kaylor combined and analyzed the results of 75 research studies on parental spanking published before June 1, 2014, they found no evidence it improves children’s behavior.

In fact, they discovered that kids spanked by their parents have a greater likelihood of experiencing 13 detrimental outcomes, including aggression, antisocial behavior, impaired cognitive ability and low self-esteem during childhood and antisocial behavior and mental health problems in adulthood.

Gershoff says children who are physically disciplined at school likely are affected in similar ways.

“There’s nothing to make me think that wouldn’t hold for corporal punishment in schools,” she says. “In fact, I think it might be more problematic in schools because of the lack of a strong relationship in the schools between the children and the person who’s doing the paddling.”

Other research by Gershoff offers insights into the types of misbehavior that lead to corporal punishment. She found that public school principals, teachers and other staff members have used physical punishment for a range of offenses, including tardiness, disrespecting teachers, running in the hallways and receiving bad grades.

Some children have been disciplined so harshly they suffered injuries, “including bruises, hematomas, nerve and muscle damage, cuts, and broken bones,” Gershoff and colleague Sarah Font write in the journal Social Policy Report in 2016.

The Society for Adolescent Medicine estimated in 2003 that 10,000 to 20,000 students require medical attention each year in the U.S. as a result of school corporal punishment. The organization has not updated its estimate since then, however.

Black students disciplined disproportionately

James B. Pratt Jr., an associate professor of criminal justice at Fisk University who also researches corporal punishment, encourages news outlets to dig deeper into the reasons schools in many states still use pain as punishment.

He says reporters should press state legislators to explain why they allow it to continue, even as public health organizations such as the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention oppose its use.

News coverage of corporal punishment needs historical context as well, Pratt says. His research finds that school corporal punishment, which is most concentrated in the U.S. South, plays a role in sustaining a long history of racialized violence in the region.

“Tell the story of corporal punishment as a form of social control,” Pratt says.

“There is research to illustrate how corporal punishment has been used historically and today.”

In the U.S., enslaved Black people were whipped, as were Black prisoners in the early 20th century and Black children who went before juvenile courts in the 1930s, Pratt and his fellow researchers write in “Historic Lynching and Corporal Punishment in Contemporary Southern Schools,” published in 2021 in the journal Social Problems.

For generations after emancipation, white supremacists in the South whipped and lynched Black people to intimidate and control them.

When Pratt and his colleagues examined data on student discipline in 10 southern states in 2013-14 and lynchings between 1865 and 1950, they learned that school corporal punishment was more common for all students — but especially Black students — in areas where lynchings had occurred.

Pratt and his coauthors write that banning school corporal punishment “would help dismantle systemic racism, promoting youth and community well-being in a region still haunted by histories of racial terror.”

Guidance from academic scholars

Both Pratt and Gershoff have lots of ideas for helping journalists frame and strengthen their coverage of corporal punishment in schools. Here are some of the tips they shared.

1. Find out whether or how schools in your area use corporal punishment, and who administers it.

Public schools generally share only basic information about corporal punishment to the U.S. Department of Education. School officials submit the total number of students they corporally punish in a given academic year and they break down that number according to students’ sex and race and whether they had a disability, were Hispanic or were enrolled in special programs teaching them to speak English.

Not only does the data lack detail — it does not indicate the type of corporal punishment used, for example, or the type of disability the student had — the information is several years old by the time the federal government finishes collecting it and releases it to the public.

Pratt says journalists can help researchers, parents and the public get a clearer picture of what’s happening in local communities by seeking out more details. To get a sense of how often and how local schools use corporal punishment, ask public school districts for copies of disciplinary reports and policies governing the use of corporal punishment.

Interview teacher union leaders and individual teachers to better understand what’s happening in classrooms and what teachers have seen and learned. Reach out to parents whose children have been disciplined to ask about student experiences.

“We know there’s something there, but how it functions on the ground is what we need to understand,” Pratt says.

Some questions to investigate:

Which misbehaviors lead to corporal punishment?

Who administers physical discipline?

What are children hit with and how many times?

Where on their bodies are they struck?

How often have children been seriously injured and how were those situations handled?

Have local schools been sued over corporal punishment?

In areas where corporal punishment is banned, have school employees been disciplined or terminated for using corporal punishment?

2. Ask how schools’ use of corporal punishment and other forms of discipline changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Students, teachers and other school staff members experienced a lot of stress during the pandemic, as schools struggled to provide instruction and other student services while also monitoring and responding to COVID-19.

At the start of the pandemic, many schools closed their campuses temporarily and taught lessons online. When everyone returned to campus, the situation was, at times, confusing or somewhat chaotic. Many schools discovered they needed to rely more heavily on substitute teachers, who often do not have classroom management training, to fill in when regular teachers were sick, in quarantine or caring for loved ones.

It’s a good idea for journalists to try to gauge how such changes have affected student behavior and discipline. Local school districts and state departments of education should be able to provide more recent records than the U.S. Department of Education. Another source of data: colleges and universities where faculty are studying school discipline.

A September 2022 analysis from the University of Arkansas, for example, shows a sharp decline in several types of student discipline in that state since before the pandemic began. However, the authors write that they “cannot tell if the decline is the result of improved student behavior or inconsistent reporting by schools.”

“Corporal punishment was used [as] a consequence for 16% of infractions in 2008-09 and declined to being used in 3% of infractions in 2020-21,” they write.

Gershoff expects corporal punishment numbers to continue to fall nationally.

“69,000 is still too many kids being traumatized at school,” she says.

There are parts of the country where school officials in recent months have reinstated corporal punishment or voiced support for it, however. Last summer, the school board in Cassville, Missouri, voted to bring it back after two decades of not using it. And a school board member in Collier County, Florida, announced after his election in November that he wanted schools across the region to reintroduce physical discipline.

3. Learn the legal history of school corporal punishment in the U.S.

It’s important that journalists covering corporal punishment understand the history of the practice, including the stance the U.S. Supreme Court and lower courts have taken on the issue.

Individual states have the authority to create and enforce discipline policies for children attending schools within their borders. Generally speaking, Supreme Court justices have been reluctant to intervene in the day-to-day operations of public schools, so long as educators do not heavily infringe on students’ constitutional rights.

Two Supreme Court cases decided in the late 1970s reinforced public schools’ right to use physical discipline. In 1975, in Baker v. Owen, justices ruled that public schools have the right to use corporal punishment without parents’ permission. In Ingraham v. Wright, decided in 1977, the court decided that corporal punishment, regardless of severity, does not violate the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.

In writing the majority opinion for Ingraham v. Wright, Justice Lewis Powell asserts that “corporal punishment serves important educational interests.”

“At common law a single principle has governed the use of corporal punishment since before the American Revolution: Teachers may impose reasonable but not excessive force to discipline a child,” Powell writes.

The Supreme Court did not, however, explain what actions would be considered “excessive.” In 1980, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit established a test for determining that. Since then, circuit courts in several federal districts have required lawsuits challenging schools’ use of corporal punishment to meet that threshold, often referred to as the “shocking to the conscience” test.

Under that very high standard, corporal punishment is deemed excessive if “the force applied caused injury so severe, was so disproportionate to the need presented, and was so inspired by malice or sadism rather than a merely careless or unwise excess of zeal that it amounted to a brutal and inhumane abuse of official power literally shocking to the conscience.”

An example of corporal punishment a U.S. appeals court decided was excessive: A football coach in Fulton County, Georgia, struck a 14-year-old freshman so hard in the face with a metal lock, the boy’s left eye “was knocked completely out of its socket,” leaving it “destroyed and dismembered.”

An example of corporal punishment an appeals court did not consider excessive: A teacher in Richmond, Virginia, allegedly jabbed a straight pin into a student’s upper left arm, requiring medical care. The court, in its ruling, notes that “most persons are with some degree of frequency jabbed in the arm or the hip with a needle by physicians or nurses. While it is uncommon for a teacher to do the jabbing, being jabbed is commonplace.”

Over the years, legal scholars have written multiple law journal articles examining the Ingraham v. Wright decision and its implications. An article by Michigan State University law professor Susan H. Bitensky, for example, looks specifically at its impact on Black children.

She argues corporal punishment has impeded Black children’s educations, undercutting the commitment to social progress the Supreme Court made when it decided in 1954, in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, that segregating public schools by race was unconstitutional.

“The whole foundation for [the Brown v. Board of Education] holding on segregated schools is a fervent concern that the schools should imbue children, especially black children, with a positive sense of their intellectual worth and should provide them with a commensurate quality of educational experience,” Bitensky writes in the Loyola University Chicago Law Review in 2004.

4. Explain that corporal punishment is a form of social control and that public schools use various types of discipline disproportionately on Black children.

Pratt stresses the importance of putting corporal punishment reports into context.

For many years, public schools have used that disciplinary approach disproportionately on Black youth, according to U.S. Department of Education records. But Black students also are disproportionately suspended, expelled, physically restrained and arrested on suspicion of school-related offenses.

According to the education department’s Civil Rights Data Collection, 37.3% of public school students who were spanked, paddled or otherwise struck by school employees in 2017-18 were Black. Meanwhile, Black kids comprised 15.3% of public school enrollment nationwide that year.

As a comparison, 50.4% of corporally punished students and 47.3% of all public school students were white.

In public preschools, black children and children with mental and physical disabilities were disproportionately expelled.

Pratt says journalists need to help the public understand how school discipline and other forms of social control such as targeted policing programs and laws prohibiting saggy pants are connected. He encourages reporters to incorporate research into their stories to illustrate how implicit bias and misperceptions about Black children can influence how educators view and interact with Black students.

Research, for example, suggests white adults perceive Black boys to be older than they are and that prospective teachers are more likely to perceive Black children as angry than white children.

“All of [these factors] relate to one another and set the tone,” Pratt says. “This is a collection of harms, and a nefarious one.”

5. Check for errors in school disciplinary reports.

Several news reports in 2021 and 2022 indicate the U.S. government’s tally of children receiving corporal punishment at school may be incorrect.

An investigation the Times Union of Albany published in September reveals hundreds of New York public school students have been physically disciplined in recent years, even though the practice has been generally banned since 1985. State and local government agencies received a total of 17,819 complaints of school corporal punishment from 2016 to 2021, 1,623 of which were determined to be substantiated or founded, the news outlet reported.

“The substantiated cases documented in state Education Department records include incidents where teachers or other staff members pushed, slapped, hit, pinched, spanked, dragged, choked or forcefully grabbed students,” Times Union journalists Emilie Munson, Joshua Solomon and Matt Rocheleau write.

A May 2021 analysis from The 74, a nonprofit news outlet that focuses on education issues, shows that schools in six states where corporal punishment had been banned reported using it in 2017-18.

Miriam Rollin, a director at the National Center for Youth Law, told The 74 that national figures “are likely a significant undercount.”

“Every school district in the country self-reports its data to the federal government and they’ve long been accused of underreporting data on the use of restraint and seclusion and other forms of harsh discipline,” Rollin told The 74 investigative journalist Mark Keierleber.

6. Press state legislators to explain why they allow school corporal punishment.

Gershoff and Pratt agree journalists should ask legislators in states that allow schools to use physical discipline why they have not stopped the practice.

“Tell the legislative story — who’s legislating this?” Pratt says. “Examine the people doing the work to end [corporal punishment] and also those wanting to maintain it.”

While a handful of members of Congress have introduced bills aimed at eradicating corporal punishment in recent years, none were successful.

In February 2021, U.S. Rep. Alcee Hastings of Florida introduced the Ending Corporal Punishment in Schools Act of 2021. But Hastings died two months later, and the bill never made it out of the House Committee on Education and Labor.

U.S. Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut introduced the Protecting Our Students in Schools Act in 2020 and then again in 2021. Neither time did the proposal go before senators for a vote.

7. Look for stories in corporal punishment data.

Browse around the U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection, which provides data on corporal punishment in public schools at the national, state and local levels as of the 2017-18 academic year. Notice trends, disparities and where there are unusually high numbers of corporal punishment cases.

For more recent data, reach out to schools, school districts and state education departments. Also, ask researchers for help explaining whether and how data from 2017-18 are still relevant.

Here are some data points worth looking into from the 2017-18 academic year, the most recent available at the national level:

Mississippi led the country in corporal punishment cases as of that year. Public schools there reported using it at least once on a total of 20,309 students. In Texas, which had the second-highest number, public schools corporally punished 13,892 kids at least one time each.

More than 30% of public school students who experienced corporal punishment in Indiana, Ohio, South Carolina and Wisconsin had mental or physical disabilities.

North Carolina public schools didn’t administer corporal punishment often. But when they did, they used it primarily on Native American students. Of the 57 students disciplined this way, about half were categorized as American Indian or Alaska Native. Native American kids made up less than 1% of public school enrollment in North Carolina.

Oklahoma is the only other state where a large proportion of corporally punished students were Native American. Schools there used corporal punishment on a total of 3,968 students, 24.4% of whom were categorized as American Indian or Alaska Native. Statewide, 6.6% of public school students were Native American.

Illinois public schools reported using corporal punishment on a total of 202 students, 80.2% of whom were “English language learners,” or children enrolled in programs to learn English.

8. Familiarize yourself with the research on corporal punishment at schools and in homes.

Gershoff points journalists toward a large and growing body of research on the short- and long-term consequences of corporal punishment at home and in schools. It’s important they know what scholars have learned to date and which questions remain unanswered.

To get started, check out these five studies:

Punitive School Discipline as a Mechanism of Structural Marginalization With Implications for Health Inequity: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies in the Health and Social Sciences Literature

Catherine Duarte; et al. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, January 2023.

This is one of the most recent papers examining the relationship between school discipline and student health in the U.S. The authors reviewed 19 studies published between 1990 and 2020 on punitive school discipline, which includes corporal punishment as well as suspension and expulsion. They find punitive school discipline is linked to “greater risk for numerous health outcomes, including persistent depressive symptoms, depression, drug use disorder in adulthood, borderline personality disorder, antisocial behavior, death by suicide, injuries, trichomoniasis, pregnancy in adolescence, tobacco use, and smoking, with documented implications for racial health inequity.”

School Corporal Punishment in Global Perspective: Prevalence, Outcomes, and Efforts at Intervention

Elizabeth Gershoff. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 2017.

In this paper, Gershoff summarizes what was known at that point in time about the prevalence of school corporal punishment worldwide and the potential consequences for students. She also discusses the various ways schools administer corporal punishment, including forcing students to stand in painful positions, ingest noxious substances and kneel on small objects such as stones or rice. She includes a chart offering estimates for the percentage of students who receive corporal punishment in dozens of countries, including China, India, Indonesia, Jamaica and Peru.

Spanking and Child Outcomes: Old Controversies and New Meta-Analyses

Elizabeth Gershoff and Andrew Grogan-Kaylor. Journal of Family Psychology, 2016.

Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor analyze the results of 75 peer-reviewed studies published before June 1, 2014 on parental spanking, or “hitting a child on their buttocks or extremities using an open hand.” They state that they find “no evidence that spanking does any good for children and all evidence points to the risk of it doing harm.”

Other big takeaways: “In childhood, parental use of spanking was associated with low moral internalization, aggression, antisocial behavior, externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, mental health problems, negative parent-child relationships, impaired cognitive ability, low self-esteem, and risk of physical abuse from parents. In adulthood, prior experiences of parental use of spanking were significantly associated with adult antisocial behavior, adult mental health problems, and with positive attitudes about spanking.”

Historic Lynching and Corporal Punishment in Contemporary Southern Schools

Geoff Ward, Nick Petersen, Aaron Kupchik and James Pratt. Social Problems, February 2021.

School corporal punishment is linked to histories of racial violence in the southeastern U.S., this study finds. The authors analyzed data on school corporal punishment in 10 states in that region during the 2013-2014 academic year and matched it with data on confirmed lynchings between 1865 to 1950. “Of the counties that reported one or more incidents of corporal punishment, 88% had at least one historic lynching and the average number of lynching incidents in these counties is 7.07,” the authors write. They add that banning school corporal punishment in these states would “help dismantle systemic racism, promoting youth and community well-being in a region still haunted by histories of racial terror.”

Disproportionate Corporal Punishment of Students With Disabilities and Black and Hispanic Students

Ashley MacSuga-Gage; et al. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 2021.

When researchers looked at student discipline in the 2,456 U.S. public schools that had used corporal punishment at least 10 times during the 2015-16 academic year, they discovered that children with disabilities were almost two times as likely to receive corporal punishment as students without disabilities. The finding is troubling, they write, considering the U.S. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act recommends schools use a behavior modification strategy known as Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports when students with disabilities misbehave.

The researchers, from the University of Florida and Clemson University, also found that Black students without disabilities were twice as likely to be physically disciplined as white students without disabilities. Meanwhile, schools were less likely to use corporal punishment on Hispanic students than white, non-Hispanic students.

Journalistsresource